Eric J Ma's Website

written by Eric J. Ma on 2024-08-09 | tags: protein engineering language models sequence generation bioinformatics protein sequence evals protein structure computational biology machine learning

This is part 3 of my three-part series on protein language models, focused on evaluations of PLMs. The previous two parts were focused on defining what a PLM is (part 1) and outlining how they are trained (part 2).

Evals, evals, evals

Once we have a trained protein language model, sequence generation becomes the easy part. What's hard is knowing which one to pick. After all, as alluded to above, we don't care as much about model training metrics (e.g. final loss) or model properties (e.g. perplexity) as we do about the performance of generated sequences in the lab. Unfortunately, my colleagues in the lab are *absolutely not* going to test millions of generated sequences to find out which handful will work, as the realities of gene synthesis and labor costs associated with assays meant to measure protein function means in most situations, we'll only get to test anywhere from 10s to 1000s of generated sequences. How do we whittle down the space of sequences to test?

The answer lies in evals. Evals are the "hot new thing" in the LLM world, but there isn't anything new under the sun here for those of us in the protein engineering world. There have been probabilistic models of protein sequences since bioinformatics became a thing (which precedes the LLM world by at least two decades), and evals of such models involved a rich suite of bioinformatics tooling: multiple sequence alignments, secondary structure prediction, motif and protein domain detection, and more that have been developed over the years. (It certainly helps that there have been decades of bioinformatics research into discovering emergent patterns within related biological sequences.) These are all tools that can be directly applied to evaluating generated protein sequences as well.

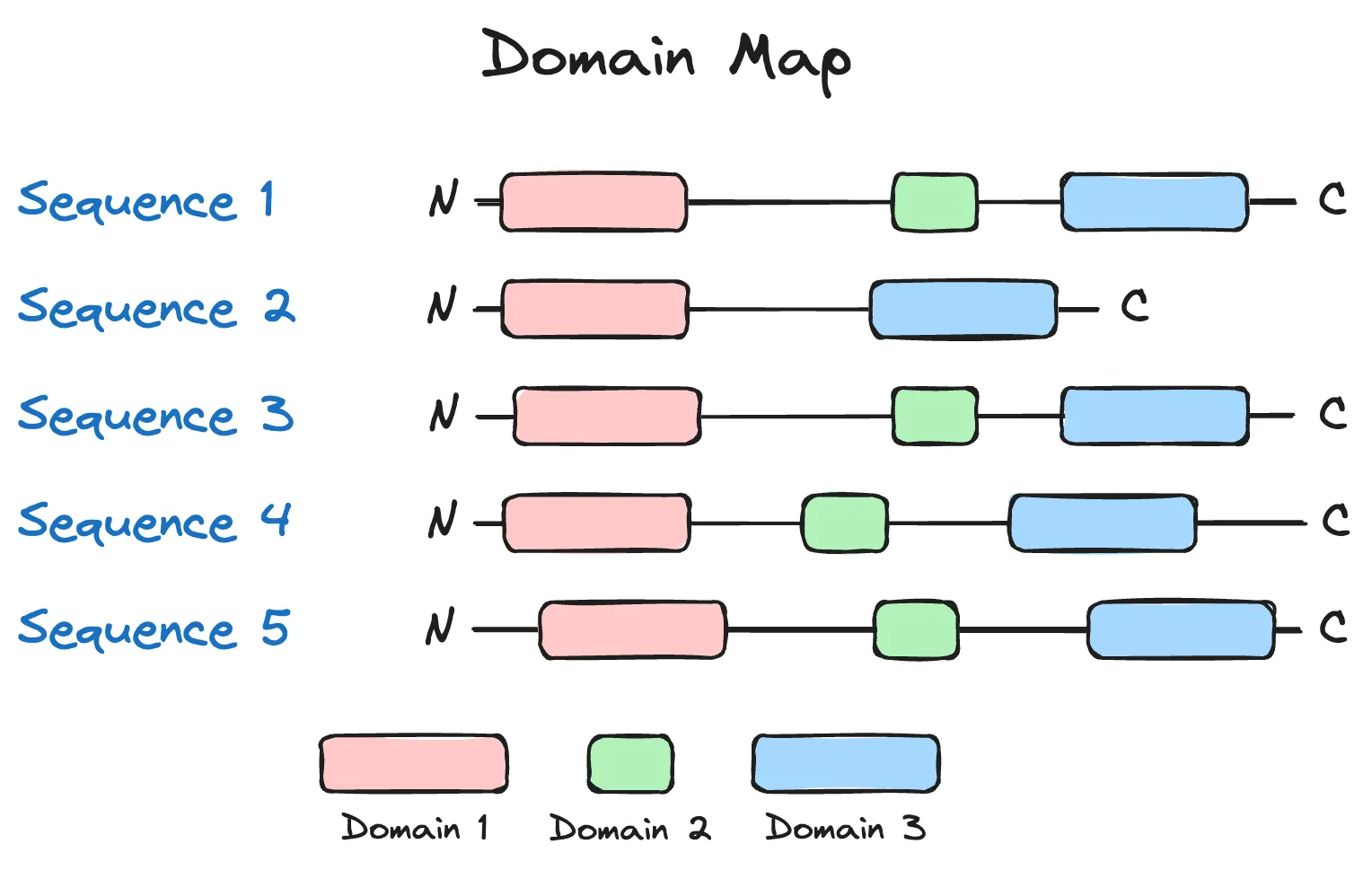

In my paper review of Profluent's preprint, I discussed using domain detection as a filter for sequences. I think this is a great illustrative example, so I'll re-hash it here (with minor edits to the original text for grammatical correctness).

If we assume that each of the sequences above was generated from a language model, and the three coloured domains were present in a naturally occurring and functional variant of the protein, then we may deduce that of the five sequences generated above, only sequence 2, which has a missing domain, may be non-functional. (There are more nuanced situations, though, such domains being unnecessary for function.) Overall, I like this idea as a sanity check on generated sequences, as a ton of prior biological knowledge is encoded in such a check.

Beyond just this single example, I wanted to outline two points when thinking about protein sequence evals. The first is that functionally, they either give us a way to rank-order sequences or they give us a way to filter them. In both cases, we can use such ranking and filtering to prioritize sequences to test in a lab. The second is that evals on generated sequences can be a leading indicator of success in protein sequence generation. Still, like all leading indicators, a key caveat remains: they are no guarantee of success in the lab!

An ontology of evals

Having thought about protein sequence evals, I would like to attempt to categorize PLM evals, particularly contextualized within the domain of protein engineering.

Sequence-based evals

These are evals that can be applied based on the sequence alone, and are applicable universally regardless of the protein that is being engineered (which is why I call them universal).

Language model pseudo-likelihoods, or the mutational effect scores as outlined above, can serve as one metric. As shown in the paper above, there are no guarantees of perfect correlation with functional activity of interest, but nonetheless they may be useful as a sequence ranker when assay data is absent. A note is that this is most easily used with masked language models rather than autoregressive models.

The Profluent CRISPR paper described degenerate sequences based on consecutive k-mer repetition. This is essentially asking if a k-mer showed up X times consecutively. Within the paper, the authors described this as no amino acid motif of 6/4/3/2 residues was repeated 2/3/6/8 times consecutively. using the first set of numbers, we didn't want to see the motif IKAVLE (or other 6-mer) repeated twice consecutively within a sequence, yielding IKAVLEIKAVLE. It should not be too hard to intuit that this kind of check can be applied regardless of the protein sequence being engineered and the property it is being engineered for. As for why this is a reasonable check, it's because such short duplications do not typically show up in natural sequences.

Also, in the same paper, we see the use of BLAST and HMMer coverage scores. These essentially ask how much the generated sequence overlaps with a target sequence or an HMM model of a collection of sequences. High coverage scores often indicate similarity to the target protein family being engineered, which can give more confidence that we have generated a plausible (and possibly functional) protein family candidate.

Another universal sanity check is the "starts with 'M' check". This stems from the observation that the letter M, representing the methionine amino acid, has a codon that is almost always universally used as the start codon when translating a protein within a cell. Once again, this check stems from general observations in nature.

Finally, sequence length is another sanity check. Autoregressive models can, sometimes, generate sequences that truncate early with a stop letter. One can hard-code a check on sequence length, such that anything, say, <70% or >130% of the reference sequence's length is automatically discarded. This stems from the observation that homologous proteins from the same family are often of similar (but not identical) lengths. That said, I pulled 70% and 130% out of my intuition, so there may be ways to use protein family-specific information (we will discuss this set of evals later) to set these length boundaries.

Structure-based evals

On the other hand, there are structure-based evals, which takes advantage of the fact that we can fold proteins in silico using models like AlphaFold2 (AF2) or ESMFold. If we have a reference protein for which we know the structure, we can use AF2 to calculate the structure of our generated sequences and compare them to the reference structure. Python packages such as tmtools can help with this task. (h/t my teammate Jackie Valeri for sharing this with me.)

If you're familiar with AF2, you may also know of a calculated metric called pLDDT, or the predicted local distance difference test. According to the EBI's AlphaFold guide,

pLDDT measures confidence in the local structure, estimating how well the prediction would agree with an experimental structure. It is based on the local distance difference test Cα (lDDT-Cα), which is a score that does not rely on superposition but assesses the correctness of the local distances (Mariani et al., 2013).

For use in evaluating AlphaFold's confidence in its structure calculation, pLDDT may be a useful metric, with scores >0.9 indicating high confidence. However, high model confidence scores does not necessarily imply a highly accurate structure, as the latter can only be evaluated using a ground truth reference. Additionally, Johnson et. al. (2023) found that for predicting enzyme activity, pLDDT was essentially uncorrelated with enzyme activity, and that:

generated sequences result in high-quality AlphaFold2 structures irrespective of their activity.

Once we have a folded structure, one can use tools like DSSP to annotate the secondary structure of a protein, such as the presence of alpha helices and beta sheets. Apart from using the TM-score to calculate the global alignment of generated structures to a reference, we can take advantage of the secondary structure annotation to ensure that, say, the order of alpha helices and beta sheets are preserved within generated sequences. This provides further evidence that a generated sequence is likely to fold correctly, which is a necessary prerequisite to function correctly.

A practical guide to collaborating

I wanted to end this essay with a few ideas on how laboratory scientists and computational/data scientists can be partners in the quest to design better proteins using protein language models. From prior experience partnering with laboratory science teams, here's what I can recommend.

For the laboratory team, be up-front about assaying capacity. There's no problem with having an assay that can only measure 10s at a time, sometimes it's just the reality of things. The computational/data scientist needs this number in order to calibrate their expectations. Consequently, the smaller the assay capacity, the more stringent the evals need to be. Engage actively in designing computable evals with the computational/data scientist. The more domain knowledge that can be encoded in a Python (or other language) program, the better the team's odds of finding great hits amongst the generated sequences.

For the computational team, be sympathetic to the laboratory assaying capacity, and design the machine learning approach to accomodate the lab testing capacity. Low N (~10s) does not necessarily negate the use of high power ML models, but it does demand more stringent checks on the sequences before sending them to be tested, because it's your laboratory colleagues' time and effort on the line. Don't blindly trust what a model gives you!

Also for the computational team, invest heavily in automation and software testing up-front. You really don't want to be in a position where you've sent sequences to the lab for testing only to find a crucial bug in your sequence generation pipeline code later. The more up-front effort you put into ensuring the correctness of the pipeline, the lower the odds of finding a fatal bug that necessitates a re-run of laboratory experiments.

For leaders, if you've read this essay, you may notice how the choices that one could make in building around PLMs are a dime a dozen. Additionally, there may be little appetite for revisiting those choices later, because their perceived impact on final selection of candidates to test might be minimal. Give your computational folks enough lead time to work with the wet lab folks to design leading indicator evaluations on generated sequences -- evals that prioritize sequences for better bets made in the lab before they are actually tested. Rushing this step will lead to tensions down the road: if the sequences turn out to be duds, it's likely because leading indicator evals weren't designed with enough input from the lab team, whose time spent is on the line. Also, give the computational team the space they need to write automated software tests for their code, as it'll dramatically reduce the chances of needing a repeat experiment.

Cite this blog post:

@article{

ericmjl-2024-a-3,

author = {Eric J. Ma},

title = {A survey of how to use protein language models for protein design: Part 3},

year = {2024},

month = {08},

day = {09},

howpublished = {\url{https://ericmjl.github.io}},

journal = {Eric J. Ma's Blog},

url = {https://ericmjl.github.io/blog/2024/8/9/a-survey-of-how-to-use-protein-language-models-for-protein-design-part-3},

}

I send out a newsletter with tips and tools for data scientists. Come check it out at Substack.

If you would like to sponsor the coffee that goes into making my posts, please consider GitHub Sponsors!

Finally, I do free 30-minute GenAI strategy calls for teams that are looking to leverage GenAI for maximum impact. Consider booking a call on Calendly if you're interested!